Technology companies like Meta, Twitter and Amazon are laying off thousands of employees as part of corporate restructuring in an uncertain global economy. In addition to jobs, many internal programs deemed unnecessary or financially infeasible may be lost. Programs that fall under the rubric of “corporate social responsibility” (CSR) are generally the first casualties of restructuring. CSR efforts include “data for good” programs designed to translate anonymized corporate data into social good and may be seen in the current climate as a way that companies cater to employee values or enable friendlier regulatory environments; in other words, nice-to-haves rather than need-to-haves for the bottom line.

We believe the platforms built to safely and ethically share corporate data to support public policy are not a luxury that companies should jettison or monetize. The data we produce in our daily lives has become integral to how public decisions are made while planning for public health or disaster response. Our 21st century public data ecosystem is increasingly reliant on novel private data streams that corporations own and currently share only conditionally and increasingly, for profit.

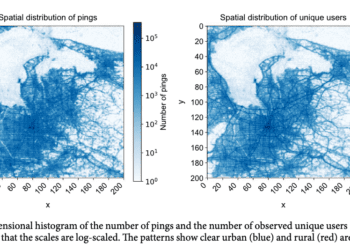

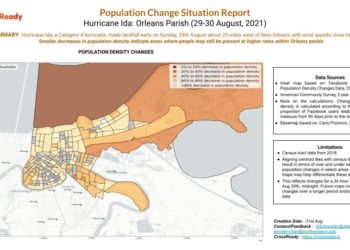

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated integration of private data into public health, particularly aggregated location data from mobile phones. This effort built upon years of research on privacy preserving algorithms, regulation, and modelling. It wasn’t only confined to the pandemic. In response to wildfires in California, for example, population mobility data is helping health agencies optimize the allocation of resources to communities in distress. Displacement maps help non profits and UN agencies like the International Organization for Migration during crises ranging from the Ukraine war to Hurricane Ian to improve targeted aid distribution. Programs like these are designed to safely share corporate data to improve people’s lives — data that would otherwise be used for marketing or not at all.

The current restructuring in the tech industry signals that these data streams are in jeopardy. They will still be traded for profit, but they may be turned off altogether in the context of public health or disaster response or become too expensive and opaque to be reliable. Many tech companies and mobile operators who initially provided public access to data have already shifted towards for-profit models of data brokerage. Whether through data companies like Safegraph or internal data marketplaces at telecoms and other firms, paywalls have gone up around data that had been freely accessible during the pandemic. Non profits and public agencies are being offered expensive data products that are difficult to compare or validate, and often lack transparency about who the data represents and how it is processed.

Many have questioned the right of technology companies to collect personal location data in the first place, arguing this information may be collected without consent or full understanding of their subsequent use. Current legal frameworks are wildly outdated when it comes to the reality of personal digital data. Privacy advocates emphasize the urgency of more comprehensive regulation. Data scientists advocate for sophisticated anonymization techniques. Others have called for community adjudication of these data in emergencies. These are critical conversations to have, engaging this entire ecosystem of actors towards agreement about when, where, and how these data should be used. Tech industry restructuring threatens these critical conversations as well.

We contend that the rapid sharing of aggregated and anonymized location data with disaster response and public health agencies should be automatic and free — though conditional on strict privacy protocols and time-limited — during acute emergencies. Technology companies will argue that they have little incentive to keep investing in these programs and are not obligated to. Likewise, data brokerages assert that sustainability of their enterprises entails high costs that must be covered somehow; however, the data themselves are essentially free, generated passively and already collected routinely.

While the challenges to realizing the full value of private data for public good are many, there is precedent for a path forward. Two decades ago, the International Space Charter was negotiated to facilitate access to satellite data from companies and governments for the sake of responding to major disasters. A similar approach guaranteeing access rights to privately held data for good during emergencies is more important now. A strong coalition of stakeholders and governance frameworks must be developed in parallel to ensure appropriate data use and continuing access, just as the world did almost 20 years ago for public rights to space-based imagery.

In a world navigating the increasing effects of climate change, novel viruses, and international conflicts, the health crises, natural disasters, and migration events we will face over the next century require that we use the very best data and analytics that can inform decision making. We cannot let the restructuring of the moment stand in the way of the tools needed to meet the challenges of the future.