This week, Direct Relief and Harvard University launched CrisisReady – a data-driven effort to inform targeted disaster response and preparedness.

The environments in which disasters occur are changing. Populations are denser. Climates are more extreme. And technology is burgeoning into new realms. These changes have ushered in a new era of disaster response.

That was the focus of an online panel Friday, convening disaster response, health and technology experts using big data to to solve public health emergencies. “How do we ensure, in this work that we’re doing, that no gets left behind?” asked Andrew Schroeder, Direct Relief’s Vice President of Research and Analysis, who moderated the panel.

“The way we approach disasters is going through a cultural shift,” said Leremy Colf, the Director of Disaster Science at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Disaster response is no longer just about what happens in the immediate aftermath of an emergency, according to Colf, but rather planning for one before it emerges.

The webinar comes as Direct Relief, in partnership with Harvard University, launches CrisisReady, a collaborative effort to coordinate streams of data from public and private actors, including international agencies such as the World Health Organization and technology platforms like Google, to inform policy decisions before, during, and after a disaster.

“Covid-19 marks a watershed moment when suddenly the world became aware that these data streams have enormous power,” said Dr. Caroline Buckee, the Associate Director of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and co-founder of CrisisReady.

Last year, Buckee worked alongside a team of researchers from Direct Relief and Harvard University to create the Covid-19 Mobility Dashboard Network, which uses anonymized population data to inform policies around social distancing, travel restrictions, and reopening timelines.

While CrisisReady works to aggregate flows of information, the emphasis is on application. “It’s not just data in a vacuum that will help address these problems,” said Alexander Diaz, the Head of Crisis Response and Humanitarian Aid at Google.org. Maps can display information about who in a community is most vulnerable to disaster, helping policy makers not only craft a more targeted response, but also promote resiliency before a crisis strikes.

For example, said Colf, emergency medical facilities often see a surge in patients after hurricanes, but preventative measures can help reduce disaster-related medical needs. “A lot of people show up at the emergency departments during disasters because there is a lack of planning.”

In the wake of a hurricane, one of the most common medical issues are asthma-induced complications, Colf has found. “A lot of the problems that we are encountering are not necessarily trauma,” he said. Based on these diagnostic trends, policy makers can determine which interventions would be most effective before a disaster, such as targeted messaging to community members or bolstering support for hospitals in medically underserved areas. “If we can target interventions to earlier times we can prevent that surge on the hospital,” said Colf.

Direct Relief will continue to share insights as CrisisReady aggregates new data flows and produces tools to inform both preventative and real-time humanitarian response efforts.

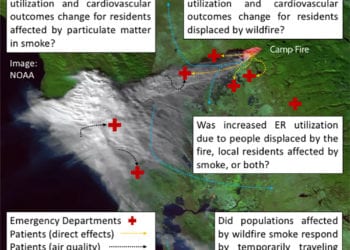

Google.org provided a $1 million grant to support CrisisReady’s “California Wildfire Project,” an effort to locate medically vulnerable populations to inform a more targeted public health response during the 2020 wildfire season.