The fifth Regional Platform for Anticipatory Action – Mitch +25 Forum – took place in San Pedro Sula, Honduras between October 31st and November 2nd. Hosted by the Coordination Centre for the Prevention of Natural Disasters in Central America (CEPREDENAC), it brought together some 200 representatives of the emergency response sector, including humanitarian agencies, risk management experts, government officials, civil society, and the private sector. Over the course of three days, participants were asked to analyze the progress achieved since the deadly path of Hurricane Mitch, as well as to create a roadmap identifying the challenges that lay ahead to promote resilience, innovation, and collaboration within the Central American Integration System (SICA).

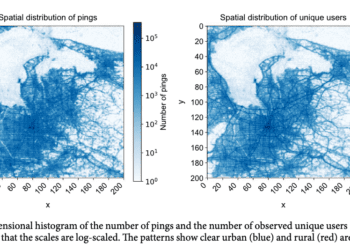

The CrisisReady and Direct Relief team joined the plenary sessions on day 1 by outlining the need and promise of mobility data in anticipatory action. Andrew Schroeder (Direct Relief; CrisisReady) exemplified this point by comparing mobility analysis for Hurricane Ian and Hurricane Otis, emphasizing how mobility data from sources like Data for Good at Meta allows response teams to evaluate evacuation dynamics, resource overload, and demographic vulnerability in near real time. There are, however, both human and technological limitations associated with this kind of analysis. Roadblocks to collaboration prevent rapid access to data; the gap between research and the public sector hinders effective methodology translation, and the lack of imperatives and incentives (both political and normative) keep data providers (often part of the private sector) unengaged.

Sources of mobility data need to be diversified to include emergency access to data from mobile network operators like Claro, Telefonica, AT&T and others. CrisisReady is currently working with CEPREDENAC and COMTELCA to develop a technological framework that supports better interagency collaboration. The framework makes use of advances in cloud computing to create digital clean rooms where data providers can securely upload their data. Agreed-upon, differentially private algorithms can then extract useful information that can facilitate the work of emergency response agencies. This architecture supports a data governance framework that addresses both corporate and user needs for privacy and provides a structure for regulatory oversight. Beyond mobility data, this approach has the potential for accommodating other sensitive and information-rich data streams, like health records.

Other introductory sessions centered discussion around the priorities outlined by the Sendai Framework. Governance of risk management got special attention. Executive Secretary of CONRED, Guatemala, Oscar Estuardo Cossío, spoke of building upon the improved articulation between different agencies by pursuing a national (Guatemalan) policy of risk management. This echoes efforts already in place by Honduras, which recently moved to create a Ministry to be filled by COPECO. According to Darío Josué García COPECO’s current Minister, this move has closed the gap between the institution’s mission of risk reduction and management and current national policy. It has yielded better access to funding and better articulation with the central government.

Funding, in particular, was raised as one of the key challenges CEPREDENAC members face when it comes to anticipatory action, given that there is little regional investment in prevention frameworks. Mauricio Paredes, current vice-president of the Honduran Red Cross, echoed COPECO’s rationale that the gap between risk management institutions and policymakers plays a key role in reduced funding, and he emphasized the need to widely share loss and damage assessments, as well as response cost estimates, with decision-makers. Finally, Claudia Herrera, president of CEPREDENAC, highlighted the need for such funding to be directed to make lasting transformational changes. The inability to properly serve vulnerable populations—a regional reality—gets exacerbated during emergency response, seriously crippling the framework of “building back better.” This is why Claudia Herrera’s emphasis on the feedback loop between risk management and regional sustainable development adequately summarizes the upcoming challenges and opportunities.

A parallel session took place in Tegucigalpa where members of SICA, the technical organ that promotes inter-sectoral coordination between SICA member states, where local universities identified points of collaboration to promote innovation within risk management. It is not clear why the meetings were held separately, given that difficulties behind the collaboration between research and the emergency management sector were a key point of discussion during several of the working groups.

Anticipation Hub, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the World Food Program discussed an array of programs geared towards early warning systems as a means of interacting with risk management. Anticipation Hub, which includes several universities, has gone a step further to create a database that collects evidence on the effectiveness of an array of early actions. This database is accompanied by several research initiatives covering a diverse range of topics from climate change to vulnerability and social protection, and has the goal of informing the selection and design of anticipatory action programs.

To bring these ideas together the CrisisReady team hosted a discussion where over 30 participants came together to identify priorities, resources, and needs around the use of science and technology for risk management. There are several state-of-the-art resources available to countries facing disasters, but these resources often stay under the radar and are not activated. The International Charter: Space and Major Disaster as an example is a venture that includes 17 space agencies and several public and private institutions that make their resources available during emergencies, but as Ricardo Quiroga from NASA’s applied science program tells us, it is rarely used. Rocio Vega, from ESRI Panamá, shared the work that has been done to try to build capacity in the use of geospatial technologies in the region, addressing one of the major roadblocks present in this area. Both the technology and the data are there, but there is a lack of technical capacity and technical management to make adequate use of these resources.

The discussion that followed revolved around three key aspects:

- The need to build networks of collaboration in service of data governance.

- The need to replace data-hunger with data-informed decision-making, and

- The need to take local knowledge generation seriously.

There was agreement that data availability is not an issue, but rather that data acquisition is often prioritized over the careful design of research questions for decision-making. Participants shared the frustration around being overwhelmed by the constant imposition of ever-evolving software and analysis tools, without patient attention to the adoption of such technologies.

This points to the fact that perhaps the barrier to technology adoption by local response teams is not merely an issue of awareness as Ricardo Quiroga suggested, but instead a matter of investing in technical capacity building to bring local actors from technology-users to technology-creators.